I was an organizer in Sudan, chosen by my community to represent their concerns to the government of our town. I was one of two women among the 40 majalis (leaders) in my town. The people I helped were very poor. Sometimes they weren’t allowed to sell their goods at the market, or in the street. Sometimes they asked me to help them get clean drinking water.

There was never enough water to drink, and it made them sick because it wasn’t clean.

That’s how my husband Mohammed became a community organizer, too. He was an engineer, working with water systems. People were having a really hard time. There was no water in some places.

He went all over the region, talking to people about their problems. He found out that salaries were too low, and in some places there was no education or medical attention.

It’s very dangerous to speak out against the government in Sudan. But my husband held meetings to organize people to improve the situation.

In the year 2000, he had to leave Sudan because the government security forces threatened his life.

My kids and I left home and went to stay with my parents.

I knew we weren’t safe there either, as soon as the security forces came and searched the house. My brother-in-law Omar brought me and our four children to the border between Sudan and Chad, and we met my husband there.

There was no party before we left.

We just cried. My parents, the kids, my brothers and sisters. We all cried.

We were leaving the blind way. Leaving our family, not knowing where we were going or what could happen along the way. It wasn’t like now, when you can find a phone anywhere.

We crossed Chad, and stayed in Cameroon for eight months.

Then we moved to Ghana, to the the Krisan Sanzule Refugee Camp, where my children and I lived for six years.

Daily life in the camp is very hard. There were a lot of refugees, and not enough supplies. The schooling wasn’t good, and there were no jobs for the refugees.

The hardest part about living in a refugee camp is that you never know about your future.

You don’t know what will happen to your kids. And you’re not doing anything. You have nothing to look forward to, you know?

The other problem is the lack of good medical care.

That’s how my husband died.

He was diabetic, but we didn’t know he had diabetes. All of a sudden, his whole body shut down. He couldn’t even walk. He just wanted to drink a lot of juice. Every morning, juice, juice, juice.

After six days like that, he passed away. I went with him to the camp hospital, then one of our friends went with him to the big hospital outside the camp. They took him to the hospital and returned him the same day—dead.

Six men carried him home.

After he died, the children and I spent four more years in Ghana. I was the only one around that could speak English. If someone spoke Arabic, I would go with them to the clinic or the hospital to interpret. I was helping other refugees from Chad and Sudan.

After six years, it was time to go to the United States.

This time we had a party.

It was just the women together. We cooked, we had coffee, we had tea. We had a cassette player. We put on Sudanese music and sang and danced. My neighbors were from Togo. They came and danced with us, too.

I was nervous about the new culture, the new place, and how I would get along with people here in the United States. Especially with six kids and no husband.

But we’re building our life here.

I’m so proud of my kids. I’m happy that my kids are all here together.

It was very hard to get them here safely.

All my neighbors tell me I have good kids. They’re very respectful. They’re all working hard in school, and trying to have a better life. My oldest son is an electrician, and wants to continue his education for that. My oldest daughter is studying at UMass Boston, in the four-year program to become a dental hygienist.

Back home, even if you go to school, that doesn’t always mean you can get a good job. The jobs are for specific people. Here in the U.S., there are many opportunities to get a good job. If you work hard, you can be somebody.

Now, I can be whatever—whoever—I want to be.

Including the person I’ve always been.

Here in the U.S., I’m still a community organizer. Everyone here in Boston has made me feel welcome. They say things like, “Nice to have you here,” and “Thank you for being here.” Even on the street, they make you feel at home!

I try to extend the same welcome to newcomers. If Arabic speakers move here, I go introduce myself, and welcome them. Then I take them everywhere, and interpret for them. Even French speakers. I don’t speak much French, but I try my best.

I feel very happy when I can help somebody.

I am also working to help other airport workers—and my own family—by organizing my union with 32BJ SEIU.

I’m a wheelchair attendant at Boston Logan International Airport. Even though I work full time and contribute to huge profits for the airlines, my kids and I have to rely on food stamps, public housing, and Massachusetts’ public health care.

I try my best to provide for them, but there’s a lot we can’t do. For example, I wish we could go on vacation together for a week—or even for three days.

That’s what our union is about. Making sure we can afford to take care of our families the right way.

We’re all here for each other. We’ll help each other. We’ll fight for each other. The union is good for all of us. It’s very important that we all participate, to improve our lives together.

See what it looks like when we stand together to protect our rights in our city, our state, and across the country.

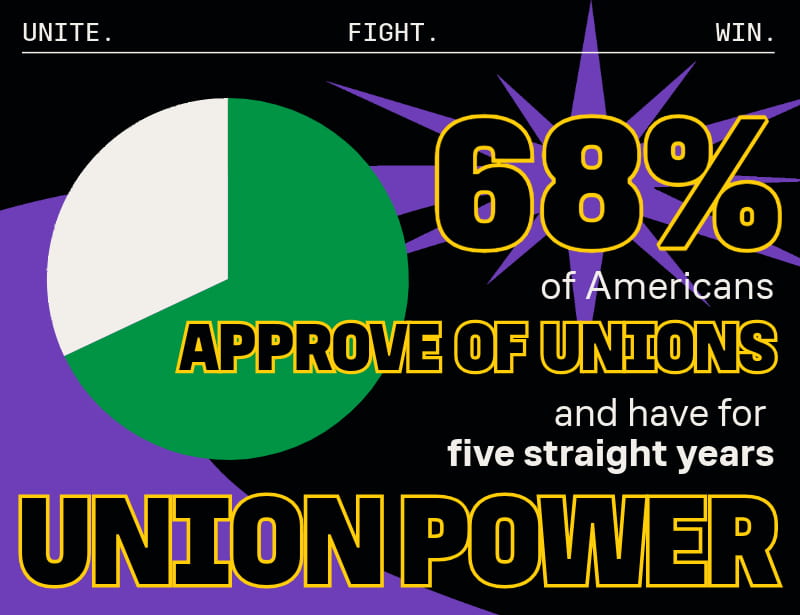

STATS